This is the first installment in a series exploring the motivations and ambitions of women municipal councillors in Ontario. It is based on data collected through email from a 116 women municipal councillors serving between 2016 and 2020.

“This is where I do my work” Women Municipal Councillors in Ontario

I chose the local level

because this is where I feel I have the most to offer (Georgian Bluffs)

I chose to run for office for a few reasons. In hindsight, ignorance also played a role in the decision, I was unaware of some of the reasons not to run for office! Reasons for: disappointment in some of the decisions made by previous municipal councils; lack of representation of youth/working age residents on council; interest in politics in general; plans to live in the community long term which I felt would benefit from involvement in local politics earlier rather than later in life (Rideau Lakes).

What

do we know about women who become municipal councillors, what motivates them,

and who are they? How do they frame themselves as political actors? It is the

purpose of these blog posts to examine the characteristics of women’s political

agency at the municipal level based on interviews with 116 female municipal

councillors in Ontario.

From

2017 to 2020, female municipal councilors were contacted though email. After

questions about age and family status, the councillors were given a set of

open-ended questions regarding their motivations, commitments, and ambitions.

The result were 116 responses ranging from several paragraphs to several pages.

The decision to set open-ended questions was to encourage respondents to share

their personal experiences and explain in some detail why they were motivated

to run, why they chose the level of government they did and what political

ambitions they held. As the questions were across email this gave a significant

amount of structure to the study which, on the one hand, limited the ability to

follow-up on answers and ask for more detail, but, on the other, allowed for a

degree of openness for sharing personal views and understandings without

overwhelming amounts of detail that would make comparisons difficult. As these

were fully-structured interviews it was much easier to compare the responses

from one councillor to another while still hearing and having access to each

individual voice. Clear patterns emerged.

The

purpose is to let the respondents speak for themselves as much as possible.

However, to list all responses would be too lengthy, cumbersome, and

repetitive. Rather quotes have been selected to be representative of the

majority, if not all, the responses. In other words, they illustrate the

pattern of common responses. In addition, quotes are selected to capture views

from smaller and larger communities, as such, statements are identified by

community rather than councillor names. (While efforts were made to ensure a

level of anonymity, the ethnographic nature of the study and the small size and

gender imbalance on particularly small councils means it is impossible to

maintain complete anonymity. Respondents were apprised of this in the ethics

disclosure that accompanied each questionnaire.)

Chapter 1: Background

To start, this

blog post sets out the general background of the councillors based on questions

regarding age and family status.

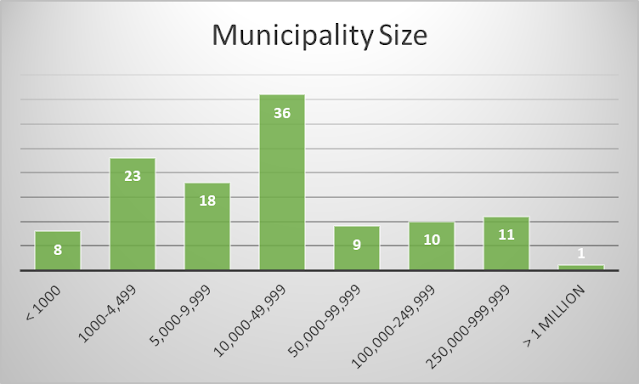

The

116 responding councillors represented communities that ranged from less than

1000 population (8 respondents) to over one million (1 respondent from

Toronto). (Municipal numbers are drawn from each municipality site on

Wikipedia, which were based on 2016 Census data.) The largest number of

respondents represented municipalities with populations between 10,000 and 49,999

(36 respondents), with 41 respondents from municipalities ranging from less

than 1000 to 9,999 people, and 31 from municipalities ranging from 50,000 to

over a million. The average size of a municipality in Ontario is 34,141, the

average number of community members represented by respondents was around 99,000.

Age:

Ages when the councillors took office ranged from

their twenties (5 respondents) to their seventies (one respondent). (One

respondent noted that her political career started when she was 16 and was

elected to student council.) The most common age for entering into politics was

in one’s forties or fifties, 37 respondents or 33% reported taking office in

their forties (40 to 49 years), while another 26%, 29 councillors, took office

in their fifties (50-59 years). Further to this, 20% (23) respondents took

office in their thirties, 17 (15%) were in their sixties, and 6 (5%) were in

their twenties.

Consequently, we can say that female municipal

councillors cover a broad range of ages between 30 and 70, with an overall

average age of 46.2. Compared to the Samara (2021) report the ages of the

respondents appear younger than when both men and women are considered. This

could be because women councillors tend to be slightly younger than their male

colleagues, which fits with observations regarding age in the federal Parliament

where both men (58%) and women (60%) are elected between the ages of 40 and 56,

and the average age for male parliamentarians is 50.5 years, while the average

age of female parliamentarians is 47.7 years (Rana 2016, cited in Newman, White

and Findley, 2020).

Marital

and Family Status:

The majority were also mothers of two or three children. Only 17 reported not having children, while the greatest number (51) had two children. 23 respondents had three children, 9 had one, while 13 reported having more than three.

Ages

of the children varied. There was a close to even split between the number who

were parents of adult children and those who had children of school age. 45

reported that their children were adults and out of the home when they entered

politics, and several reported being proud grandparents. 47 reported having

school aged children when they took office, 25 had grade-school kids (ages 6 to

12 years), and 22 had kids in high school (13 to 18) years.

This

did not mean that mothers of young children were missing as municipal

councillors, 4 reported having infants under two years and 13 were mothers of

pre-school toddlers aged 2 to 5 years.

However,

the relatively small numbers of mothers of young children confirmed the

observation that women are far more likely to enter politics when their

children have left home as adults or need less attention as they are

self-catering and at school for a significant portion of the day.

Past Experience:

While the councillors were not asked specifically about their backgrounds, they were asked if they had held an elected position prior to running. This was to establish how many had served as school board trustees before entering council. Only 6 reported to have originally served as school board trustees, and one stated she had previously served as a member of provincial parliament. Beyond this, past experience for many of the respondents could be extrapolated from their general responses, particularly in the statements outlining their motivations for running. Therefore, the numbers in the table below do not represent individuals but the number of times the various backgrounds and experiences were raised in the collected statements.

Nearly all of the respondents described their backgrounds as being in small-p rather than large-P politics. It is useful to make a distinction between large-P politics, which are associated with the affairs of state and the activities of political parties, and small-p politics which are characterized by grassroots informal consensus-based face-to-face community-building (Newman and White, 2012, p. 86, Siim 1994, and Bellah, et. al., 1985). Small-p politics reflects intimacy and proximity to families and friends, a vision that is more “democratic” and “open access” valuing access to elected representatives for the community and access to the community for elected representatives (Crow,1997). This is agency that is about community-building and development, reached through face-to-face discussions where citizenship is virtually coextensive with getting involved with one’s neighbours for the good of the community (Bellah, 1985). We shall discuss this more fully as the series goes on.

The findings in this study correspond to the Samara (2021) findings that only a minority of local politicians take an explicitly political path through advocacy, partisan involvement, or holding other office. Here most of the respondents spoke of coming to local office as a natural progression from their volunteer work.

The volunteer service described throughout the survey was a mix of charitable organizations, business organizations, environmental organizations, and local committees and boards. A larger number discussed being attached to advocacy groups, but these were specifically local in nature focusing on community poverty, environmental issues, ad business. The pattern was of general civic engagement, rather than party political engagement.

The next post in this series will look at the

motivations stated by the respondents.

References

Bellah, Robert N, Richard Madsen, William M. Sullivan, Ann Swidler, and Steven M. Tipton. 1985. Habits of the Heart: Individualism and Commitment in American Life. New York: Harper and Row.

Crow, Barbara. 1997. ‘Relative

Privilege? Reconsidering White Women’s Participation in Municipal Politics,’ in

Cathy J. Cohen, Kathleen B. Jones, & Joan C. Tronto (eds.) Women

Transforming Politics: An Alternative Reader. New York: New York University

Press, pp. 435-446

Jacquetta Newman and Linda White. 2012. Women, Politics and Public Policy: The

Political Struggles of Canadian Women, 2nd Edition. Don Mills: Oxford

University Press.

Jacquetta Newman, Linda White & Tammy Findley.

2020. Women, Politics and Public Policy: The Political Struggles of Canadian

Women 3rd Edition. Don Mills:

Oxford University Press.

Rana, Abbas. 2016. ‘‘We Live in a

globalized world,’ House most ethnically diverse in Canadian History, but still

has long way to go: research’. Hill Times, 21 November 2016.

https://www.hilltimes.com/2016/11/21/mps-50-59-age-group-26-mps-four-children-politics-common-field-study-majority-mps-study/88112

Samara. 2021. Locally Grown: A survey of municipal

politicians. (January 2021) Available at:

https://www.samaracanada.com/research/political-leadership/locally-grown

Siim, Birti. 1994. “Engendering Democracy: Social

Citizenship and Political Participation,” Social Politics (1994), pp.

286-305.

Comments

Post a Comment